Gather ‘round, children of the Perpetual Upgrade Cycle! Let Ol’ Processor Pete spin you a yarn. It starts, as all modern fairy tales do, under the blinding lights of a minimalist stage. A charismatic CEO in a tragically hip black turtleneck holds aloft the New Thing™. Maybe it’s the iPhone 17S Ultra Max Plus, now 0.02 millimeters thinner and available in Cosmic Mauve. The crowd gasps. The tech blogs explode with orgasmic headlines like “Revolutionary!” and “Game Changer!” You, sitting there bathed in the blue light of your current device (suddenly feeling woefully inadequate), feel that familiar itch. That gnawing, consumerist craving whispering sweet nothings: You need this. Your life will be meaningless without Cosmic Mauve.

So you buy it. You stand in line, or frantically click refresh, securing your place in the glorious march of progress. You unbox its sleek perfection, marvel at its slightly faster processor, take a selfie with its marginally improved camera. And the old one? Your trusty companion of yesteryear, the iPhone 16X Pro Deluxe? It gets tossed in a drawer, maybe traded in for a pittance, or eventually dropped off at some vaguely defined “recycling point.” You feel virtuous. You did the right thing.

Except you didn’t. You just bought a one-way ticket for your old gadget to the hottest vacation destination you’ve never heard of: The E-Waste Archipelago.

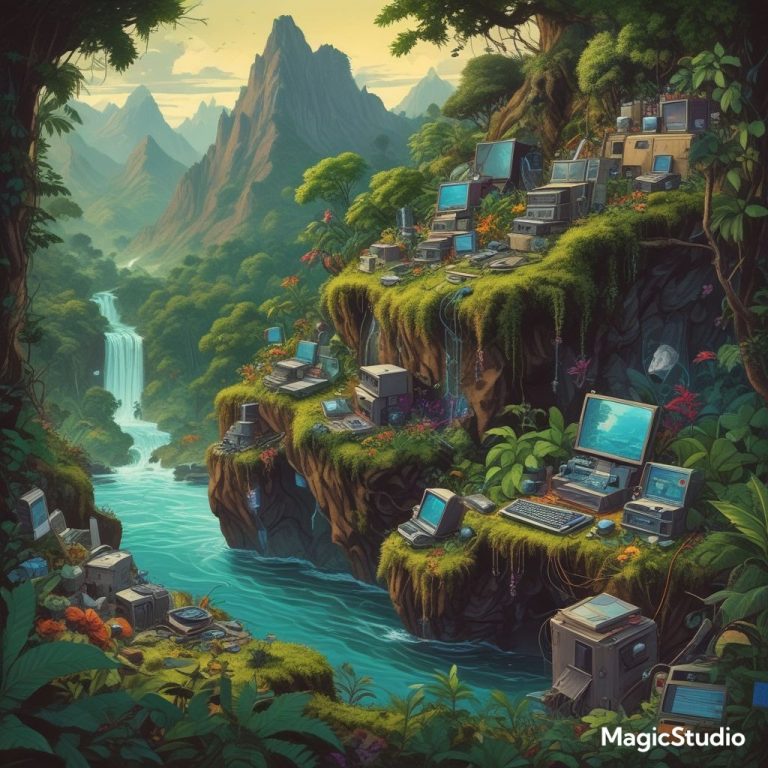

Forget the Bahamas, forget Fiji. This archipelago isn’t dotted with palm trees and pristine beaches. It’s a sprawling, informal network of digital graveyards, festering sores on the backside of the planet, likely located somewhere conveniently out of sight and mind – think Agbogbloshie in Ghana, Guiyu in China, or maybe some newly terraformed hellscape funded by venture capital called “Resource Reclamation Zone Omega”¹. These are the places where your technological marvels go not to be reborn through the miracle of recycling, but to die a slow, toxic death, leaching heavy metals and carcinogenic fumes into the earth, air, and water. So it goes.

The journey itself is a marvel of modern logistics, a reverse Silk Road paved with discarded circuit boards. Forget gleaming cargo planes; picture rusty container ships, flags of convenience flapping listlessly, piled high with the ghosts of gadgets past². They’re crammed with cracked screens, dead batteries, obsolete motherboards – the digital detritus of our relentless desire for the new. Shipped under deliberately vague customs declarations like “Used Goods” or “Plastic Scrap,” it’s the biggest shell game on the planet, making sure the toxic buck stops somewhere far, far away from Cupertino or Seoul.

Once arrived at the Archipelago, the real fun begins. Forget the slick, automated disassembly lines you might imagine. Here, the “recycling” often involves open-air burning of plastic casings and wires to get at the meager scraps of copper and aluminum within. Picture plumes of acrid black smoke blotting out the sun, a scene worthy of Mordor, but fueled by discarded Fitbits instead of Orcish industry. Kids, sometimes barefoot, scavenge through mountains of electronic guts, smashing cathode ray tubes (remember those?) that release plumes of lead dust, bathing in a toxic cocktail of cadmium, mercury, beryllium, and flame retardants³. It’s a Dead Kennedys album cover brought terrifyingly to life: Plastic Surgery Disasters meets Holiday in Cambodia, but the holiday destination is a literal dump.

And the companies that flooded the world with this stuff? Oh, they’re very concerned. They issue glossy sustainability reports thicker than phone books, boasting about their “commitment to a circular economy” and their “take-back programs.” These programs often account for a statistically laughable percentage of the actual waste – maybe 15-20% on a good day, according to a study probably funded by the Guatemalan Tourism Board pretending to be an environmental watchdog⁴. The rest? Well, that’s handled by “certified third-party partners,” a convenient layer of abstraction that allows MegaGadget Corp. to wash its hands clean while the downstream consequences pile up like, well, mountains of e-waste. Their definition of “recycling” seems suspiciously close to “making it someone else’s problem, preferably someone poor and far away.”

Let’s talk numbers, because numbers make the absurdity quantifiable. Globally, we generate something like 50 million tonnes – that’s metric tonnes, folks – of e-waste every year. That’s like throwing out 1,000 laptops every second. And the rate is climbing faster than a Silicon Valley startup’s valuation before the inevitable crash. Projections suggest we’ll hit over 74 million tonnes annually by 2030⁵. Where is it all going? Hint: Not to a magical farm upstate where old electronics frolic happily. It’s going to the Archipelago.

The marketing machine demands this sacrifice. How else can they justify selling you essentially the same device year after year, differentiated only by a slightly tweaked camera lens or a new shade of pretentious metallic paint? Planned obsolescence isn’t a bug; it’s the core operating system of modern consumer electronics. Software updates conveniently slow down older models. Repair is actively discouraged through proprietary screws, glued-in batteries, and extortionate parts pricing. They want you to throw it away and buy the new one. The entire business model depends on this cycle of desire, consumption, and disposal.

It’s Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians observing human folly, but instead of war, it’s the relentless pile-up of toxic junk. We create these intricate, resource-intensive devices, marvels of engineering containing precious metals mined under horrific conditions, only to render them obsolete within a couple of years and ship their toxic corpses overseas to poison vulnerable populations. The E-Waste Archipelago isn’t just an environmental catastrophe; it’s a monument to our collective short-sightedness, our addiction to novelty, and the grotesque externalization of costs that underpins late-stage capitalism.

So next time you feel that upgrade itch, next time Chad McSterling unveils the Cosmic Mauve Miracle Device™, pause for a second. Think about where your old phone is really going on vacation. It’s not sipping piña coladas by the beach. It’s contributing to a toxic bonfire somewhere you’ll never see, releasing fumes that might circle the globe, impacting people you’ll never meet. But hey, at least your new phone is 0.02 millimeters thinner. Progress!⁶ So it goes.

Footnotes:

¹ Internal Memo – OmniCorp Waste Solutions Division: “Project Archipelago successful. Offshore ‘Resource Reclamation Zones’ operating at 98% capacity below regulatory oversight threshold. Recommend rebranding from ‘E-Waste Dump’ to ‘Circular Economy Material Hubs’ for Q3 shareholder report.” Source: Recovered from a corrupted hard drive labeled “Plausible Deniability Archive.”

² Shipping Manifest Excerpt (Translated): “Contents: Assorted Plastic Housings for Refurbishment. Origin: Everywhere. Destination: Somewhere Else. Value: Negligible (for tax purposes).” Actual Contents: 20 tonnes of hazardous electronic scrap.

³ Field Report – Unspecified NGO: “…children exhibiting alarming rates of respiratory illness, skin lesions, and developmental problems. Soil and water samples show lead levels 400 times WHO safety limits. Air quality comparable to inside an active volcano during a tire fire.” Conclusion: Further study needed (pending funding, unlikely).

⁴ “The Phantom Loophole: Assessing Efficacy in Global Tech Take-Back Initiatives,” Journal of Convenient Assumptions, Vol. π: This deeply optimistic (and likely industry-funded) paper used advanced statistical modeling (read: guesswork) to conclude that corporate recycling programs are “generally trending in a positive direction,” despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.